Topics mentioned: anxiety, perfectionism, self-esteem, counselling and therapy

About: Annabell, 21, explains how counselling and CBT helped her understand perfectionism, break anxious thought cycles, and put her wellbeing first.

On the surface, perfectionism looks like a need for excellence, but at its core it can be fuelled by a lack of self-esteem and internal reference.

My anxiety always made me feel like my life had two parts: negatives and positives. Anything negative became part of an endless string of mistakes that were always, always due to some innate fault of mine. Any positives were simply accidents, or because I'd somehow managed to perfectly follow the rules anxiety dictated for me.

When I was younger, that anxiety was wrapped up in a playful nickname, something my mum would tell other parents who were amazed by me: that I was “a perfectionist”. As I grew older, and the stressors of exams, uni and life began to take their toll, the pressure made my worries all the more intense.

What is perfectionism?

On the surface, perfectionism looks like a need for excellence, but at its core it can be fuelled by a lack of self-esteem and internal reference. Perfectionists often think in rigid, critical patterns that, overtime, can skew their values, beliefs and behaviours - both about themselves or towards others.

Not only did this harm my self image, but it made it difficult for me to take care of myself, especially in periods of poor mental health.

For me, this meant the way I saw myself was based on how I assumed other people saw me. I’d struggle to describe myself, or name things I liked about myself without defaulting to things related to someone else, e.g. being creative so other people thought I was, and liked me for it, was more important to me than actually making art and enjoying the process.

It was like I didn’t exist as a whole person - I’d just pick a version of me to play for whoever was watching. I would worry about making mistakes because I didn’t want to disappoint or inconvenience people by falling short of their expectations, not out of any concern for myself.

Not only did this harm my self image, but it made it difficult for me to take care of myself, especially in periods of poor mental health. All my energy and time went to preserving this construct of myself I’d created.

I realised that the daily burden of trying to satisfy these standards wasn't propelling me towards anything, but instead holding me back.

The idea that changed my perspective

In my first year of university, a depressive episode kept me out of lectures for weeks. I remember the counsellor I saw at the time introduced me to this idea: that perfectionism wasn't something I 'had', but a placeholder for everything it was costing me.

My self-doubt and self-criticism weren’t innate, unchangeable parts of myself, they were behaviours I’d developed overtime to try to cope with my anxiety, that ultimately made it worse. The effort I was putting into monitoring and overworking myself could be used for things that would actually make me happy.

I realised that the daily burden of trying to satisfy these standards wasn't propelling me towards anything, but instead holding me back. I was stuck in a projection of my self-image based on a throwaway comment from when I was five years old.

It was difficult to accept at first. The rules and expectations I'd created for myself had been a barrier to hurt, failure and any form of disappointment for so long. Reaching out for help felt like stabbing my younger self in the back. At first, I couldn’t separate myself from my perfectionist tendencies: I believed I owed them everything. Behind every achievement was the fear that had motivated me to work hard. Without that, I was nothing.

At last, I felt that my life wasn’t something I had to prove the value of; I had so much to be proud of without even trying.

CBT and questioning my anxious thoughts

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) helped me make sense of these conflicting feelings and start working on finding who I was outside of my expectations. My therapist encouraged me to think outside of myself:

-

"What kind of person did my friends think I was?"

-

"What kind of person did I want to be?"

Seeing that my personality and identity didn’t have to be tied to achievements at school or abstract ways of being 'the best' helped me regain a sense of direction. At last, I felt that my life wasn’t something I had to prove the value of; I had so much to be proud of without even trying.

Perfectionism isn’t a logical mindset, and once you start to poke holes in it, it’s easy to see that. Working through thought cycle exercises with my therapist empowered me to question my anxious thoughts and stop giving in to behaviours that I knew would hurt me in the long run. It was difficult, but it helped me see my thought processes laid out.

For example, forcing myself to work through assignments at night would always stop me from sleeping; sleep deprivation would make my work worse or incomplete; and ultimately stop me from attending class, keeping the cycle of worry in play. This confirmed that I was only hurting myself and feeding into my fear. I could never worry my way into success.

Letting go of my own rigid expectations and prioritising my wellbeing (sleeping regardless, doing half of the work, not beating myself up for being five minutes late or not going at all), was the only way to escape the cycle.

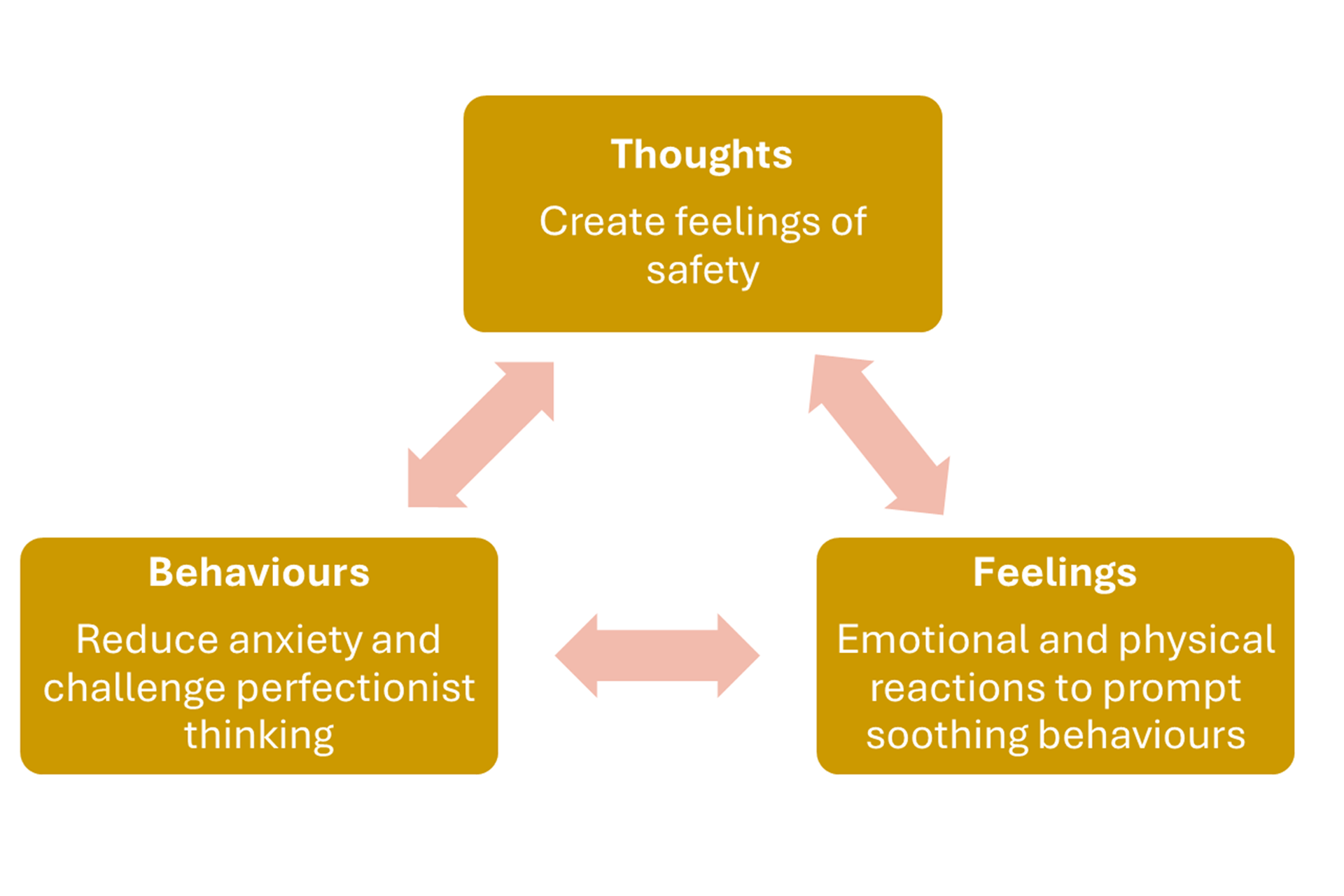

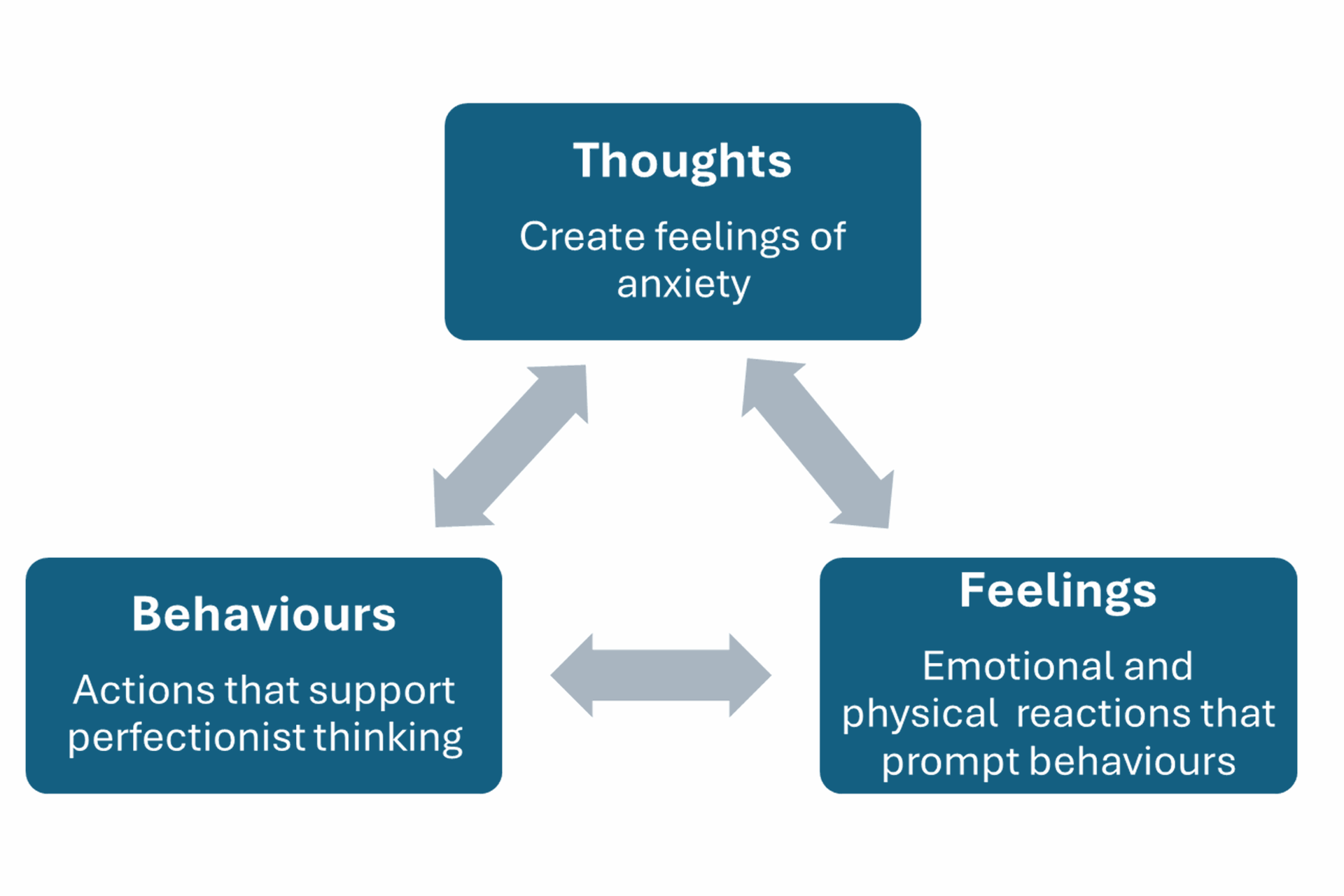

Once a situation initiates a cycle, here are two examples of what a thought cycle can look like:

Three boxes connected by arrows to show a safety thought cycle. The first box reads, 'Thoughts create feelings of safety'. The second box reads, 'Feelings. Emotional and physical reactions to prompt soothing behaviours'. The third box reads, 'Behaviours. Reduce anxiety and challenge perfectionist thinking.'

Three boxes connected by arrows to show an anxious thought cycle. The first box reads, 'Thoughts create feelings of anxiety'. The second box reads, 'Feelings. Emotional and physical reactions that prompt behaviours'. The third box reads, 'Behaviours. Actions that support perfectionist thinking'.

Small steps can make a big difference

Coping with anxiety isn’t a one-way street. I’m in my third year of uni now and I still find myself confronting the same fears around making mistakes as I was in secondary school. The difference now, of course, is that I’m willing to confront my anxiety, rather than give in to it. Even if tasks end up taking a little longer, I’m willing to be kind to myself and find a mindful, non-self-destructive way of doing things.

It’s hard work, but taking even one small step in the right direction already takes you further away from anxiety, and closer back to yourself.

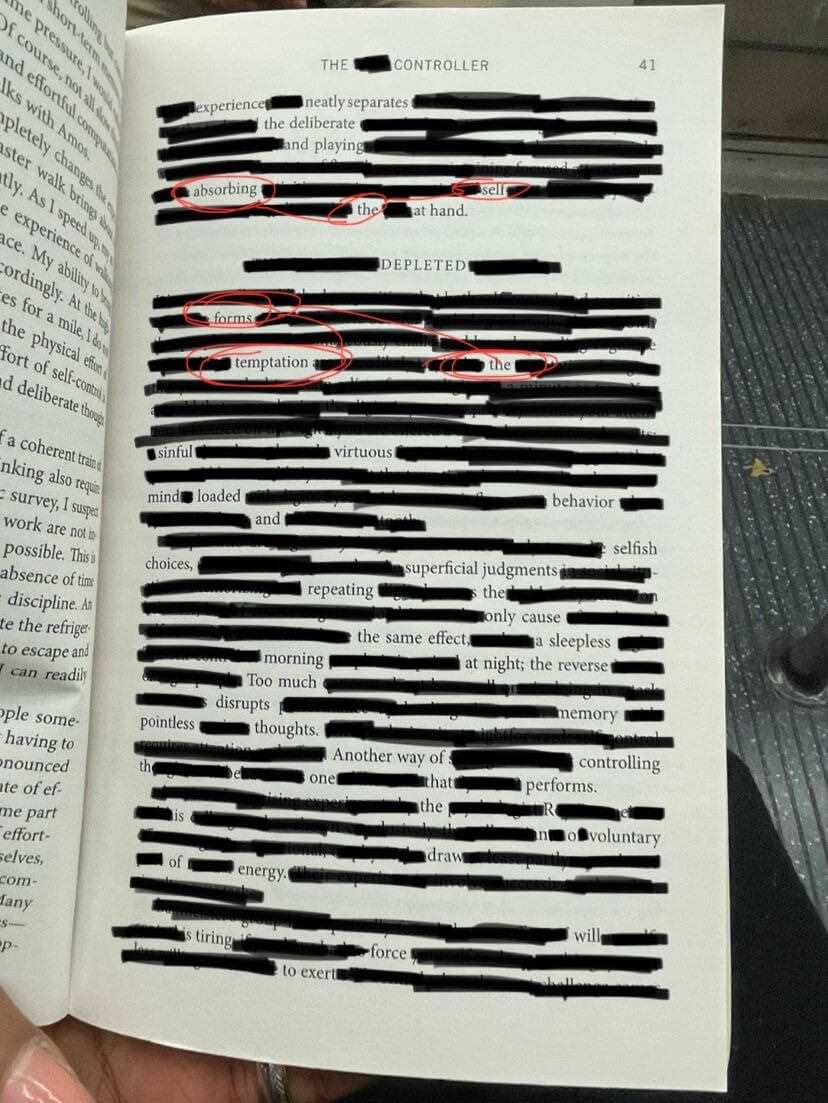

This is a blackout poem that I wrote about anxiety and perfectionism.

The Controller

experience

neatly separates

the deliberate

and playing,

absorbing the self at hand.

DEPLETED, temptation forms

the

sinfunl,

virtuous

mind,

loaded behaviour and selfish choices

superficial judgements

repeating

the only cause

the same effect

a sleepless morning; at night the reverse

too much disrupts memory

pointless thoughts - another way of controlling

the one that performs -

there is no voluntary draw of energy:

will is tiring force to exert.

More information and advice

We have tips and advice to help you find the support you need. Take a look at our guides.

Where to get help

However you're feeling, there are people who can help you if you are struggling. Here are some services that can support you.

-

The Mix

Free, short-term online counselling for young people aged 25 or under. Their website also provides lots of information and advice about mental health and wellbeing.

Email support is available via their online contact form.

They have a free 1-2-1 webchat service available during opening hours.

- Opening times:

- 4pm - 11pm, Monday - Friday

-

CALM (Campaign Against Living Miserably)

Provides support to anyone aged 16+ who is feeling down and needs to talk or find information.

Free webchat service available.

Read information about the helpline and how it works.

- Opening times:

- 5pm - midnight, 365 days a year

-

Tellmi

Formerly known as MeeToo. A free app for teenagers (11+) providing resources and a fully-moderated community where you can share your problems, get support and help other people too.

Can be downloaded from Google Play or App Store.